Introduction: The Cell’s Amazing Copying Machine

Before any cell can divide to create two new daughter cells, it must first perform one of life’s most fundamental tasks: making a perfect copy of its DNA. Think of DNA as the master blueprint containing all the instructions needed to build and operate an organism. If you were to build a new factory, you wouldn’t give it a partial or incorrect set of blueprints; you would give it an exact duplicate of the original. In the same way, a cell must copy its entire genome with incredible precision.

This is a monumental task. Replicating all of the DNA in a single human cell takes several hours, considering that there are almost three billion base pairs of DNA to be copied. This process, called DNA replication, is essential for biological inheritance, cell division, and the continuity of life, ensuring that each new cell receives the exact same genetic information as its parent.

1. The Foundation: Understanding DNA’s Structure

To understand how DNA is copied, we first need to understand its structure. The DNA molecule is famously a double helix, which can be visualized as a twisted ladder.

• The two long “rails” of the ladder are known as the sugar-phosphate backbones.

• The “rungs” connecting the rails are pairs of nitrogenous bases. There are four types of bases in DNA: Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T).

• The two strands are anti-parallel, meaning they run in opposite directions. This is described by a naming convention called 5′ (five-prime) to 3′ (three-prime). If one strand runs in the 5′ to 3′ direction, its partner runs in the 3′ to 5′ direction.

The secret to DNA’s ability to be replicated lies in how these bases pair up. The rule is strict and is known as complementary base pairing.

| Base on Strand 1 | Complementary Base on Strand 2 |

| Adenine (A) | Thymine (T) |

| Guanine (G) | Cytosine (C) |

This unwavering rule means that the sequence of bases on one strand is a perfect template for the sequence on the other. If you know the sequence of one strand, you automatically know the sequence of its partner. With this perfect template in hand, the cell employs an elegant and efficient method to create the two new copies.

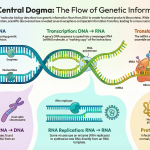

2. The Big Picture: What “Semi-Conservative” Means

DNA replication is a semiconservative process. This term sounds complex, but the idea is simple. When a DNA molecule is copied, it first unwinds into its two original strands. Each of these original strands then serves as a template to build a brand-new complementary strand.

The result is two identical DNA double helices. Each new helix consists of one original strand and one newly synthesized strand. This elegant mechanism ensures that the original template strands remain intact and are passed down through many cell generations.

3. The Process Step-by-Step: Building a New DNA Molecule

DNA replication is a highly coordinated process that occurs in three main stages, carried out by a team of specialized enzymes.

1. Initiation: Finding the Starting Line Replication doesn’t just start anywhere on the DNA molecule. It begins at specific locations called an origin of replication.

• The process kicks off when an enzyme called Helicase attaches to the DNA. Its job is to act like a high-speed zipper, breaking the weak hydrogen bonds between the base pairs and “unzipping” the double helix at rates of up to 1000 nucleotide pairs per second.

• This unzipping action creates a Y-shaped structure known as the replication fork, which is the active site where DNA synthesis will occur.

• As the strands separate, proteins called single-strand binding proteins (SSBPs) quickly coat the exposed bases to prevent the two strands from snapping back together and to protect them from damage.

2. Elongation: Building the New Strands. With the template strands exposed, the primary “builder” enzyme, DNA polymerase, gets to work. This enzyme has two critical characteristics:

• It synthesizes the new DNA strands by reading the template and adding new, complementary nucleotides.

• It can only build in one direction: the 5′ to 3′ direction.

However, DNA polymerase can’t start from scratch. It needs a starting block to build upon.

• An enzyme called Primase creates a short RNA primer, which is a small stretch of nucleotides that marks the starting point for DNA polymerase.

The “5′ to 3′ only” rule for DNA polymerase means that the two new strands at the replication fork must be synthesized in slightly different ways.

• The Leading Strand This new strand is synthesized continuously as one long piece. This is possible because it is built towards the replication fork, following Helicase as it unzips the DNA.

• The Lagging Strand This strand presents a puzzle. The anti-parallel template strand runs from 3′ to 5′, but DNA polymerase can only build in the 5′ to 3′ direction. This ‘5’ to 3′ only’ rule creates a seemingly impossible challenge. To solve this, the cell uses a clever “backstitching” strategy. Because this strand must also be built in the 5′ to 3′ direction, synthesis must proceed away from the advancing replication fork. As a result, the lagging strand is built discontinuously, in a series of short segments called Okazaki fragments. Each fragment requires its own RNA primer to get started. After the fragments are synthesized, another enzyme, DNA ligase, acts as a molecular “glue” to join the Okazaki fragments together, creating a complete, continuous strand.

3. Termination: Finishing the Job The process ends when the replication forks meet each other (on a circular chromosome) or when they reach the end of a linear chromosome.

• In eukaryotes (like humans), the ends of linear chromosomes are called telomeres. These are regions of repetitive DNA sequences that help prevent the loss of important genes during each round of replication, as the machinery can’t copy the very tips of the chromosome.

4. Meet the Molecular Machinery: A Summary of Key Players

To keep track of the main enzymes, here is a simple summary of their roles.

| Enzyme | Primary Function (Simplified) |

| Helicase | Unzips the DNA double helix to separate the two strands. |

| Primase | Creates a short RNA primer to mark the starting point for DNA synthesis. |

| DNA Polymerase | The main builder adds new nucleotides to create the new DNA strands and proofreads its work. |

| DNA Ligase | The “gluer”; joins the Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand into a continuous strand. |

5. The Importance of Accuracy: Proofreading and Precision

DNA replication is not just fast; it is also incredibly accurate. This high fidelity is essential to prevent harmful mutations. The primary mechanism for this accuracy is the proofreading ability of DNA polymerase.

If DNA polymerase accidentally adds an incorrect nucleotide, it can pause, “back up,” and use an exonuclease activity to remove the mismatched nucleotide. It then tries again, inserting the correct base. This self-correcting mechanism, along with other cellular repair systems, results in a remarkably low error rate of about one mistake for every billion nucleotides copied.

To appreciate how extraordinary this is, consider that other key cellular processes, such as RNA or protein synthesis, have an error rate of about 1 in 10,000—a rate 100,000 times greater than that of DNA replication. This 5′ to 3′ direction is also crucial for efficient error correction; a hypothetical 3′ to 5′ polymerase would be unable to correct an error without halting synthesis entirely.

Conclusion: The Unbroken Chain of Life

DNA replication is a masterpiece of molecular engineering. It is a highly efficient and accurate process carried out by a machine-like complex of cooperating proteins and enzymes. By using each original strand as a template, this process guarantees the precise transmission of genetic information from one generation of cells to the next. This fundamental mechanism is the very basis of heredity and the unbroken chain that connects all living things.

Image Summary

References

Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. DNA Replication. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9940/

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. DNA Replication Mechanisms. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26850/

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/health-and-medicine/dna-replication