Introduction: The Cell’s Scribe

Imagine a cell’s DNA as a vast, master cookbook containing all the recipes the cell will ever need to build and maintain itself. Each gene is like an individual recipe for a specific protein. This master cookbook is too valuable to leave its central, protected archive (the nucleoid region). So, when a particular recipe is needed, the cell sends a scribe to carefully copy it onto a small, portable note card. This note card can then be taken to the cell’s kitchen to be read.

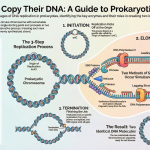

This process of copying a gene’s recipe from the DNA cookbook onto an RNA note card is called transcription. It is the first and most fundamental step in gene expression, the process of turning genetic information into a functional product. This article will break down how this remarkable process works in prokaryotes (like bacteria) through three clear stages: Initiation, Elongation, and Termination.

1. Setting the Stage: The Key Players in Prokaryotic Transcription

Prokaryotic cells, which include bacteria, are models of efficiency. Because they lack a nucleus, the cellular machinery for reading the RNA note card (translation) can begin its work even while the note card is still being copied (transcription). This simultaneous process allows bacteria to respond with incredible speed to changes in their environment.

The process of transcription involves two main participants: the enzyme that does the copying and the DNA signal that marks the starting point.

• The Scribe: RNA Polymerase This enzyme is the molecular machine responsible for building the RNA message. It reads the DNA blueprint and assembles a complementary RNA strand. RNA polymerase exists in two key forms:

◦ Holoenzyme: This is the complete, active complex, made of the Core Enzyme plus a crucial helper protein called the Sigma (σ) Factor. The holoenzyme is essential for starting transcription because the sigma factor is what recognizes the starting line of a gene.

◦ Core Enzyme: After transcription has begun, the sigma factor detaches, leaving the core enzyme to continue building the rest of the RNA strand.

• The Blueprint: The DNA Promoter A promoter is a specific sequence of DNA located just upstream of a gene. It acts as a “start here” sign, telling the RNA polymerase holoenzyme exactly where to bind and begin copying. Prokaryotic promoters have two critical parts, known as consensus sequences because they are very similar across different genes and bacterial species.

| Promoter Element | Consensus Sequence | Primary Function for the Learner |

| -35 Region | TTGACA | Acts as the primary docking site that the Sigma (σ) Factor recognizes and binds to. |

| -10 Region | TATAAT | Rich in Adenine (A) and Thymine (T), this sequence is easier to unwind, allowing the DNA to open up to be read. |

The more closely a promoter’s -35 and -10 regions match these consensus sequences, the more strongly and frequently RNA polymerase will bind, leading to higher levels of gene expression.

Biologists use a specific numbering system for genes. The DNA nucleotide where transcription begins is called the +1 site, or the initiation site. All DNA sequences ‘before’ this site (in the direction of the promoter) are referred to as upstream, while sequences ‘after’ it are downstream.

With the stage set and the key players introduced, let’s watch the three acts of transcription unfold.

2. The Three Acts of Transcription

Act I: Initiation – Getting Started

Initiation is all about getting the RNA polymerase correctly positioned at the promoter and prying open the DNA double helix so the recipe can be read. This happens in a precise sequence of events.

1. Finding the Start Line: The sigma (σ) factor, as part of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme, scans the DNA until it recognizes and binds to the -35 and -10 promoter sequences. At this point, the DNA is still a fully zipped-up double helix. This initial structure is called the closed complex.

2. Opening the Blueprint: The high concentration of A-T base pairs in the -10 region makes it easier to pull the two DNA strands apart, as A-T base pairs are held together by only two hydrogen bonds, compared to the three bonds holding G-C pairs together. The enzyme unwinds this section of DNA, creating a small “bubble” where the template strand is exposed. This structure is now called the open complex.

3. A Few False Starts: The polymerase sometimes struggles to get going. It begins synthesizing very short strands of RNA, about 10 nucleotides long, in a process called abortive initiation. These short transcripts are not functional and are released without the polymerase moving from the promoter.

4. Promoter Escape: Once the polymerase successfully synthesizes an RNA strand longer than 10 nucleotides, it achieves a stable hold on the DNA. It breaks its bonds with the promoter sequence and begins to move forward. At this point, the sigma (σ) factor detaches. Its job—getting the process started correctly—is done. The core enzyme is left to carry out the rest of the task, officially beginning the next stage.

Act II: Elongation – Building the Message

With initiation complete, the core enzyme enters the elongation phase—the main event of transcription. During this stage, the full RNA copy of the gene is built.

The RNA polymerase core enzyme moves along the DNA template strand, acting like a train on a track. It continuously unwinds the double helix ahead of itself and rewinds the DNA that it has already transcribed behind it.

As it moves, it reads the template strand one nucleotide at a time and adds the corresponding complementary RNA nucleotide to the 3′ end of the growing message. This means the new mRNA strand is synthesized in the 5′ to 3′ direction. The polymerase is remarkably efficient, moving at a speed of approximately 40 nucleotides per second. While highly efficient, RNA polymerase also has a modest proofreading ability; it can detect and remove an incorrectly matched nucleotide before continuing, ensuring a reasonable level of accuracy in the final mRNA message.

Act III: Termination – The Final Stop

The cell doesn’t want to waste energy copying DNA forever, so there must be a clear “stop” signal. Termination is the process that tells the RNA polymerase to halt, release the newly made mRNA message, and detach from the DNA. Prokaryotes use two main strategies to accomplish this.

Strategy 1: Rho-Independent Termination

This is a clever, self-termination mechanism that is written directly into the DNA sequence of the gene. It relies on two key features that are transcribed into the end of the mRNA molecule:

• First, the polymerase transcribes a C-G rich region of DNA. The resulting mRNA sequence immediately folds back on itself, as the complementary C and G nucleotides bind together to form a stable hairpin loop. This structure acts like a brake, physically stalling the polymerase.

• Immediately following the hairpin sequence, the DNA template has a string of adenine (A) nucleotides. This creates a corresponding string of uracil (U) nucleotides in the mRNA. The U-A bonds that temporarily hold the mRNA to the DNA are very weak.

The combination of the stalled polymerase (caused by the hairpin) and the weak U-A connection is unstable enough for the core enzyme to break away, liberating the completed mRNA transcript.

Strategy 2: Rho-Dependent Termination

This mechanism requires the help of a specialized terminator protein called the Rho factor.

• The Rho factor protein binds to the growing mRNA strand and begins moving along it, “chasing” the RNA polymerase.

• Near the end of the gene, the polymerase encounters a specific stretch of guanine (G) nucleotides on the DNA template, which causes it to stall.

• This pause gives the Rho factor time to catch up. When the Rho factor collides with the stalled polymerase, it acts to pull the new mRNA transcript away from the DNA template, releasing it from the transcription bubble and ending transcription.

Now that the mRNA message is complete, prokaryotes can take advantage of a unique feature of their cellular design to put it to work immediately.

3. The Prokaryotic Advantage: Unmatched Speed and Efficiency

One of the defining features of prokaryotes is their lack of a nucleus. While this might seem like a simple structural difference, it allows for a process of incredible efficiency: simultaneous transcription and translation.

In a bacterial cell, as the RNA polymerase moves along the DNA transcribing an mRNA molecule, ribosomes can attach to the 5′ end of the very same mRNA and begin translating it into protein. In other words, the protein recipe is read and cooked while the note card is still being written. This remarkable coupling is physically possible because both transcription (mRNA synthesis) and translation (protein synthesis) proceed in the same 5′ to 3′ direction, allowing ribosomes to latch onto the ‘front end’ of the mRNA while the ‘back end’ is still being created. Multiple ribosomes can translate the same mRNA at once, creating many copies of the protein from a single transcript.

This coupling of transcription and translation allows a bacterial cell to amplify a protein’s concentration with astonishing speed, enabling a rapid and robust response to environmental cues.

4. Conclusion: The Message is Ready

Prokaryotic transcription is a beautifully regulated, three-act play designed for maximum speed and efficiency. It begins with Initiation, where the RNA polymerase holoenzyme recognizes a specific promoter on the DNA and prepares it for copying. This is followed by Elongation, where the core enzyme faithfully synthesizes the RNA message. Finally, in Termination, specific signals encoded in the DNA—either forming an RNA hairpin or interacting with a Rho factor—instruct the polymerase to stop and release the finished product.

The central purpose of this entire process is to create a mobile, disposable copy of a gene’s permanent instructions. This mRNA “note card” is now fully prepared to be read by the cell’s protein-building machinery in the next essential step of gene expression: translation.

Image Summary

References

Zhou, D., Yang, R. Global analysis of gene transcription regulation in prokaryotes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 2260–2290 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-006-6184-6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bacterial_transcription

https://www.nursinghero.com/study-guides/wmopen-biology1/prokaryotic-transcription-and-translation

https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax)/3%3A_Genetics/15%3A_Genes_and_Proteins/15.2%3A_Prokaryotic_Transcription

Seshasayee, A.S.N., Sivaraman, K., Luscombe, N.M. (2011). An Overview of Prokaryotic Transcription Factors. In: Hughes, T. (eds) A Handbook of Transcription Factors. Subcellular Biochemistry, vol 52. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9069-0_2

https://web.archive.org/web/20191114234353/https://opentextbc.ca/biology2eopenstax/chapter/prokaryotic-transcription/

van Hijum SAFTMedema MH, Kuipers OP 2009. Mechanisms and Evolution of Control Logic in Prokaryotic Transcriptional Regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00037-08