Nature is rife with astonishing examples of self‑healing—species that regenerate damaged parts or even treat their wounds naturally. In this article, we’ll explore verified cases of animals using innate regenerative powers or self‑medication, shedding light on nature’s wisdom and its potential implications for human medicine.

1. Orangutan applying medicinal plant poultice

In 2024, scientists documented a Sumatran orangutan named Rakus deliberately chewing leaves of Fibraurea tinctoria and applying the juice and plant pulp to a facial wound. The plant has known antibacterial and anti‑inflammatory properties, and Rakus’s wound healed fully within days—an unprecedented observation of self‑medication in a wild great (Laumer et al., 2024).

2. Chimpanzees using chewed leaves for wound care

Chimpanzees in Uganda’s Budongo Forest were observed licking their wounds and applying chewed leaves—some with medicinal benefits—and even assisting unrelated peers in wound care. Researchers documented dozens of self‑treatment cases and social care, suggesting a cultural knowledge of healing plants passed in social groups (Freymann et al., 2025).

3. Dolphins rubbing against corals or sponges

Indo‑Pacific bottlenose dolphins have been seen rubbing on specific corals and sponges with bioactive compounds. Studies suggest these interactions help prevent skin infections or wounds, indicating dolphins may self‑medicate using environmental resources (Morlock et al., 2022).

4. Axolotls regrowing limbs, organs, even brain tissue

The Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) is capable of regenerating entire limbs, spinal cord segments, heart, parts of brain, and eye tissue—without scarring. They form a blastema at wound sites, where undifferentiated cells rebuild complex structures. Their inflammation suppression and regenerative signaling mechanisms make them key models in biomedical research (Walker et al., 2025).

5. Planarian flatworms and hydras: masters of regeneration

Planarians can regenerate entire individuals from mere body fragments, thanks to neoblasts—pluripotent stem cells. Likewise, hydras rebuild whole bodies from small pieces. Both organisms illuminate fundamental mechanisms of regeneration in stem‑cell research (Levin et al., 2019).

6. Starfish and sea cucumbers regenerating entire bodies or organs

Starfish can regrow lost arms—and in some species, even whole bodies from an arm fragment—via pluripotent cells and slow reconstruction over many months. Sea cucumbers can eject internal organs (evisceration) as a defense, then fully regenerate them in weeks—a dramatic example of organ regrowth.

7. Sharks: rapid wound healing and organ regeneration

Sharks rapidly heal from open wounds—even large ones—without infection. Certain species (e.g. white‑bamboo shark) can regenerate up to two‑thirds of their liver in days, facilitated by immune genes, fast clotting, and stem‑like responses (Wei et al., 2021).

8. Spiny mice and deer antler regrowth

Spiny mice (Acomys) are among the few mammals able to regenerate skin, cartilage, and hair follicles without scarring, highly unusual among mammals. Meanwhile, deer annually regrow complex bone structures (antlers) rapidly, providing a mammalian example of bone regeneration (Riddell et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025).

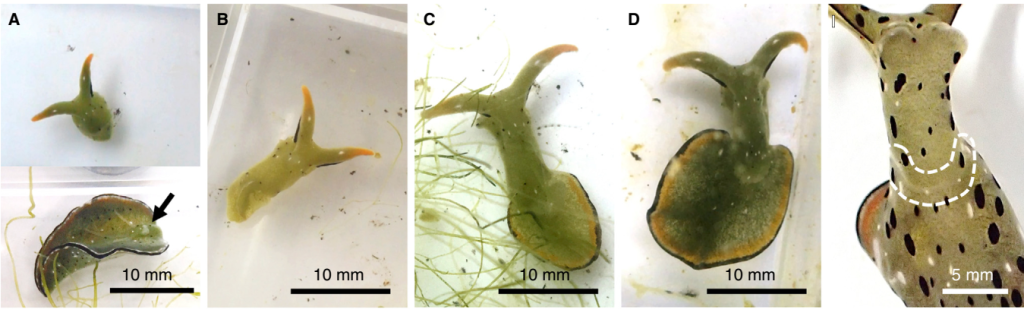

9. Sea slugs that decapitate themselves and regenerate whole bodies

Sacoglossan sea slugs (e.g. Elysia species) self‑autotomize their body (leaving only the photosynthesizing head with stolen chloroplasts), then regenerate the rest of the body, sometimes multiple times. This extreme adaptation may help purge parasites or survive serious predation injuries (Mitoh and Yusa, 2021).

Here’s an extended list of animals that use self-medicating behavior, known as zoopharmacognosy, with additional examples beyond the ones already provided:

Mammals:

- Chimpanzees – Eat bitter leaves (Aspilia, Vernonia) to treat parasitic infections and intestinal worms.

- Orangutans – Rub their fur with Dracaena plants, likely for anti-inflammatory properties.

- Elephants – Consume certain plants to induce labor or relieve digestive issues.

- Capuchin Monkeys – Rub millipedes on their fur to repel insects and prevent fungal infections.

- Baboons – Eat Opuntia cactus pads to soothe digestive issues.

- Gorillas – Consume plants with medicinal properties, such as Vernonia, to expel worms.

- Brown Bears – Rub their fur against tree bark, particularly with resin from pines, which can have antiseptic properties.

- Wolves and Coyotes – Eat grass and certain plants to induce vomiting or ease digestive problems.

- Bats – Some species consume specific plants to alleviate parasitic infections.

- Domestic Dogs – Eat grass to induce vomiting and help with digestive discomfort.

- Moose and Deer – Eat specific plants, like willows rich in salicylic acid (an aspirin-like compound), to relieve pain and fever.

- Squirrel Monkeys – Rub their fur with aromatic plants, such as Piper leaves, which have antibacterial properties.

- Mountain Gorillas – Consume specific types of clay and medicinal plants to detoxify their diets and manage parasites.

- Wild Boars – Rub their skin in mud that contains plants with antibacterial properties, possibly to treat skin irritations.

- Bighorn Sheep – Consume toxic lichen to rid themselves of parasites, despite the risk of toxicity.

- Mountain Goats – Lick certain types of clay or minerals to alleviate pain or neutralize toxins in the plants they consume.

- Horses – Are known to seek out specific herbs in the wild when they feel unwell, such as dandelion and burdock.

- Cats – Chew on catnip and other plants, not just for pleasure but also potentially for their mild calming effect and digestive relief.

- Manatees – Have been observed rubbing themselves against rocks or coral to scratch off parasites, possibly helping to heal skin issues.

- Primates (Multiple Species): Beyond chimpanzees and orangutans, other primates, like howler monkeys, have been observed consuming toxic plants in small doses to purge parasites.

- Rodents – Some studies have shown that wild rodents selectively consume plants with antifungal properties to protect their nests.

Birds:

- Parrots (Amazon parrots, Macaws) – Ingest clay (geophagy) to neutralize toxins from their food.

- Crows and Ravens – Rub ants on their feathers, which release formic acid to eliminate parasites.

- Starlings – Line their nests with aromatic herbs to repel parasites and bacteria.

- European Jays – Select specific plants like yarrow to use in their nests for parasite control.

- House Sparrows – Use cigarette butts in their nests to reduce mite infestations, as nicotine acts as a pesticide.

- Pigeons – Ingest small stones (gastroliths) not only for digestion but potentially to help absorb toxins.

- House Finches – Have been observed using cigarette butts in nests for their pesticidal properties.

- Blue Tits and Great Tits – Steal nicotine-laden tobacco leaves and use them in their nests to repel parasites.

Insects:

- Honeybees – Use propolis (plant resin) in their hives to disinfect and protect against fungal and bacterial infections.

- Ants – Some species collect resin from trees with antifungal properties to protect their colonies from disease.

- Woolly Bear Caterpillars – Feed on toxic alkaloid-rich plants to kill internal parasites.

- Monarch Butterflies – Lay eggs on milkweed, whose toxins protect their larvae from parasites.

- Leaf-Cutting Ants – Use antimicrobial substances to keep their fungal gardens healthy.

- Fruit Flies – Lay eggs on alcohol-rich fruits to protect larvae from parasitic wasps.

- Termites – Apply their saliva, which contains antimicrobial compounds, to their nests to control fungal growth.

- Sawflies – Larvae consume resin-rich plants that may deter predators and parasites.

- Drosophila Flies (Fruit Flies) – Lay their eggs in alcohol-rich environments to prevent parasitism from wasps.

- Honeybee Larvae – Benefit from propolis, which their colony collects and uses to disinfect the hive and fight off bacteria.

Fish:

- Wrasse Fish – Engage in mutualistic behavior with cleaner fish to remove parasites and dead skin, effectively “medicating” themselves.

- Tang Fish – Visit cleaner fish stations to rid themselves of parasites.

- Guppies – Have been observed selectively consuming plants with antiparasitic properties in experimental settings.

Reptiles and Amphibians:

- Green Iguanas – Eat clay to detoxify their food, especially when they consume plants high in tannins.

- Snakes (Various species) – Rub against rough surfaces or engage in basking to help remove parasites and dead skin.

Invertebrates:

- Crickets – Eat moldy food with certain fungi that protect from parasites.

- Wood Ants – Incorporate resinous plant material in their nests to prevent fungal infections.

- Beetles (Leaf beetles) – Some species store plant-derived chemicals to protect against microbial attacks.

Marine Animals:

- Dolphins – Rub against coral or sponges that release antibacterial and antifungal substances to treat skin irritations.

- Sea Otters – Use specific rocks to crack shellfish but also rub certain types of seaweed on their bodies, which might serve as a form of parasite control.

- Whale Sharks – Visit cleaner stations where smaller fish clean their skin, removing parasites and dead tissue.

- Cleaner Shrimp – Not only clean parasites off fish but also may provide a medicinal benefit by nibbling dead tissue and promoting healing.

- Caribbean spiny lobsters have been observed using a communal den structure that may reduce disease transmission among individuals.

Behavioral Variations:

- Tool Use for Medicinal Purposes: Animals like capuchin monkeys and orangutans are known to use tools (sticks or leaves) not only for foraging but also to apply medicinal substances, such as insect-repelling plants, to their bodies.

Human Observations of Animal Medicine:

- Domesticated Animals: Even domestic pets, such as cats and dogs, may instinctively seek certain grasses or herbs when experiencing digestive distress, although not as sophisticated as their wild counterparts.

The study of animal self-medication is ongoing, and the discovery of new behaviors across species highlights the complexity and widespread nature of zoopharmacognosy. There’s likely more to uncover in other animal groups or in more specific ecosystems that haven’t been deeply explored yet.

Conclusion

From orangutans using medicinal plants to sea slugs regrowing bodies, these examples of animal self‑healing and natural regeneration reveal life’s resilience and adaptability. These behaviors—whether regeneration or zoopharmacognosy—offer insights into evolutionary medicine and future therapeutic avenues for humans.

References

Mitoh, S., & Yusa, Y. (2021). Extreme autotomy and whole-body regeneration in photosynthetic sea slugs. Current Biology, 31(5), R233-R234. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.014

Laumer, I.B., Rahman, A., Rahmaeti, T. et al. Active self-treatment of a facial wound with a biologically active plant by a male Sumatran orangutan. Sci Rep 14, 8932 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58988-7

Freymann, E., Hobaiter, C., Huffman, M. A., Klein, H., Muhumuza, G., Reynolds, V., … & Carvalho, S. (2025). Self-directed and prosocial wound care, snare removal, and hygiene behaviors amongst the Budongo chimpanzees. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1540922. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2025.1540922

Morlock, G. E., Ziltener, A., Geyer, S., Tersteegen, J., Mehl, A., Schreiner, T., … & Brümmer, F. (2022). Evidence that Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins self-medicate with invertebrates in coral reefs. IScience, 25(6). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104271

Walker, S. E., Yu, K., Burgess, S., & Echeverri, K. (2025). Neuronal activation in the axolotl brain promotes tail regeneration. npj Regenerative Medicine, 10(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00413-2

Levin, M., Pietak, A. M., & Bischof, J. (2019, March). Planarian regeneration as a model of anatomical homeostasis: recent progress in biophysical and computational approaches. In Seminars in cell & developmental biology (Vol. 87, pp. 125-144). Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.04.003

Wei, L., Wang, M., Xiang, H., Jiang, Y., Gong, J., Su, D., … & Shi, J. (2021). Bamboo shark as a small animal model for single domain antibody production. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 9, 792111. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.792111

Riddell, B., McDonough, M., Ferguson, A., Kimani, J. M., Gawriluk, T. R., Peng, C., … & Seifert, A. W. (2025). Complex tissue regeneration in Lophuromys reveals a phylogenetic signal for enhanced regenerative ability in deomyine rodents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(1), e2420726122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2420726122

Guo, Q., Zhang, G., Ren, J., Li, J., Wang, Z., Ba, H., … & Li, C. (2025). Systemic factors associated with antler growth promote complete wound healing. NPJ Regenerative Medicine, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00391-5